by Amber Parker

Two and a half years ago, I was a recreational student at SANCA, studying aerial fundamentals and growing exponentially as a person through circus arts. I found things at SANCA I never thought I’d find: community, joy, healing, and a question that I couldn’t stop asking myself: Can circus be used as mental health therapy?

I shared this question with Jo Montgomery, SANCA’s founder, and she said, “I’ve always thought circus could be a great mental health treatment, but that’s not my area of expertise. I’m really excited you’re thinking about this.” Then she handed me a copy of Women’s Circus: Leaping Off The Edge, a book about a women’s circus troupe in 1990’s Australia that used circus arts education as a way to confront childhood trauma and heal as a community. After reading this book, I had an answer to my question: Yes, circus arts can absolutely be adapted and expanded to become a multidisciplinary creative arts therapy.

Today, I am a coach at SANCA in the Every Body’s Circus program and attend Antioch University where I am earning a dual Master’s Degree in Couples and Family Therapy and Drama Therapy. I work primarily with adult women, often plus size women, who want to use circus arts as a way to re-connect with their bodies and support their mental health. By studying and coaching congruently I am in a unique position to learn counseling and psychology theory and apply it in my coaching practice, which deepens my understanding and work at SANCA. However, it’s my students, and not theory, that teaches me most about what it means to heal. After two quarters of working to create SANCA’s very own Women’s Circus, I’d like to share with you the lessons my students have taught me so far.

Body work is emotional work

Every time we sweat, get out of breath, stretch, bend, or otherwise become embodied, we remember the stories of our body. For survivors of trauma, these body memories can trigger trauma related responses, such as panic, irritability, anger, or feelings of insecurity. In the 2014 novel, The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma, Bessel A. van der Kolk, says,

“Traumatized people chronically feel unsafe inside their bodies: The past is alive in the form of gnawing interior discomfort. Their bodies are constantly bombarded by visceral warning signs, and, in an attempt to control these processes, they often become expert at ignoring their gut feelings and in numbing awareness of what is played out inside. They learn to hide from their selves.” (p.97)”

When your experiences with struggle and pain are connected to past or current experiences of abuse, addiction, or mental health issues, and not healthy things like physical activity, we avoid pain and struggle at all costs. Thus, we learn to avoid the struggle and pain of exercise, too. However, struggle is an unavoidable truth of life, as is physical and emotional pain. Circus teaches us about healthy struggle, we experience pain that is normal and non-abusive. When my students become angry, frustrated, or triggered, we stop. We talk about what’s happening with them on an emotional level. Sometimes, we cry. It’s part of the journey.

Coach Amber works with her student Shannon on the trapeze.

A big part of the work we do in Women’s Circus centers around the idea that the way you do one thing is the way you do everything, thus, the way we approach circus is emblematic of the way we approach life. For instance, when a student is struggling with confidence in her ability to learn circus skills, we will take time to discuss how that struggle shows up in other parts of her life. One of my first students, Shannon Callahan, has used the trapeze not only to get in touch with her physical self, but her emotional self, too.

Shannon says, “The emotional piece really comes in when we talk about how the trapeze represents life. I keep going back to that. When I go through something emotionally difficult, I now ask myself, ‘How is this problem like the trapeze?’ And I always find a connection. So, now, I ask myself- how would I deal with this if I were on the trapeze? How do I overcome it? How do I work with it, accept it, embrace it? How do I evolve?”

With every lesson my students teach me more and more about the emotional messages that live in our body and how they come through when we move. I’ve found that by making space for emotional processing during lessons, we can unpack those messages in a supportive, non-shaming environment. Instead of living in fear of ourselves, circus teaches us mastery over struggle and lets us reclaim our bodies and hearts from trauma.

Adults Need Play, Too

It turns out the play is just as important for adults as it is for children. Play is a vital component to the process of learning and growing, and since we never stop learning and growing, adults need it, too. In an NPR piece about the importance of play, Dr. Stuart Brown of the National Institute of Health states, “Play is something done for its own sake…it’s voluntary, it’s pleasurable, it offers a sense of engagement, it takes you out of time. And the act itself is more important than the outcome.”

Mary tries out a trick on the lyra.

Indeed, this reflects what one of my students, Mary Dempsey, said to me when I asked her why circus is healing: “I get to play here. I’m not just surviving.”

When I play with my students, I see them transform. The laugh, they yell, they delight in their bodies. A student who comes in heavy with sadness leaves bright, exhilarated, and beaming. When I watch my students play I see them write a new story about themselves — that they are resilient, they are strong, than can change. My student, Cassidy Sweezey, is a great example of how playing at SANCA brings her relief, happiness, and connection to her body.

Cassidy says, “Today I wasn’t very motivated to do anything athletic or fun at all, but just coming here and being in this environment, messing around and playing, all of a sudden we’re moving and learning skills and having fun. It’s contagious. Just being around everyone here is inspiring; no matter what they’re doing. I’ve never experienced any stress or discomfort here, so my body just goes into a state of feeling safe and comfortable. I felt awful when I got here, I felt really depressed and bummed out, but now I feel really good.”

Visibility is Revolutionary

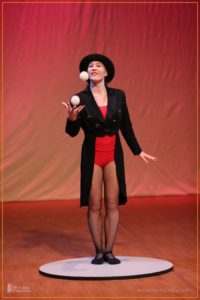

Amber and Cassidy after a great circus class.

We live in a society that tells women they are not enough. Not thin enough, successful enough, valuable enough. When these messages are reaffirmed through traumatic experiences, we believe them to be true. If our culture, family, or intimate partners have told us these stories about ourselves throughout life, we literally do not have any other script about who we are. The way I see these messages come in students is most often through poor body image or shame about their size. I remember what it was like to be the token fat girl in my first circus class, how othering that was. I was lucky, though, to have other fat women in my life who showed me there’s not just one way to have a body. Similarly, through circus arts my students confront what it means to be in a body society tells us is unhealthy and shameful.

My student Shannon says, “Because of my size, I try to hide. I try to become smaller. But, when I leave circus, I hold my head higher. I take up space, I feel bigger. I deserve that.”

With every catchers hang, straddle back, or elbow bridge, they destroy the notion that fat equals unhealthy. Whether they know it or not, when my students dare to be fat, active, and visible, they not only give other women permission to do the same, they challenge a pervasive, destructive cultural narrative about size.

Recently, a child in nearby class watched a student of mine on the trapeze and said to his coach, “But…big people can’t do trapeze,” to which she replied, “Yes, they can. Watch them.”